Sadly, Vancouver artist, Ian McKay, has passed on. He could only be described as “larger than life.” He started out as a mime artist and never lost his flair for the theatrical: full of life, quick to laugh, a friend to many. If you ever met Ian (and because he told everyone), you would know that he was the opening act for a Led Zeppelin concert and performed with Cheech and Chong at the burlesque house, The Shanghai Junk. Around that time he took a fundamental art course, but found it too academic (and boring). Instead, he taught himself to draw by studying the old masters. This soon led to his first painting exhibit in Toronto in 1972.

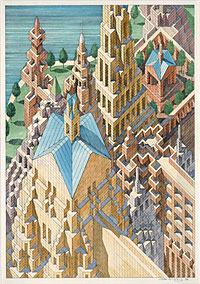

Ian was a prolific painter, but the quirky brilliance of his work was the Tower of Babel project. Although Ian developed macular degeneration, which left him legally blind, he hand-drew these works (with a large magnifying glass) until the very end. This is how Ian described his fantastical, imaginary drawing project he called “Axonometropolis”.

Axonometropolis is a city of the imagination; infinite in structures, roads, canals and bridges as if in a daydream.

I have been working on The Babel Project for twenty years. I was inspired by the writings of the blind author Jorge Luis Borges. Ironically perhaps, like him, I am nearly blind.

When inventing the Library of Babel, Borges said that the universe is a sphere whose centre is everywhere and circumference nowhere. I am imagining the City of Babel. Babel was to be constructed to reach Heaven; and so, for me, it must be built to infinite scale.

Axonometropolis is a term I invented to describe a city which can only exist as an axonometric drawing, which describes mass, volume and spatial relationship without perspective. Therefore, there are no vanishing points or horizon. The buildings, pathways, lakes and gardens are visible in their actual scale, in all directions, to infinity.

Until 2010 I was drawing only the “districts” of Babel. Now the districts are expanding into each other, forming larger areas where the viewer can get a greater sense of my ultimate goal.

Because I am nearly blind, I can only create one small area at a time, using a magnifier. The drawings started in 2008 are improvised directly, in ink, freehand without a plan.

Ian’s work did not go unnoticed. His drawings were included in a beautiful book, Visionary Architecture: Unbuilt Works of the Imagination (1999, Ernest Burden, McGraw-Hill). He was one of the amazing artists included in this book, which featured the famous 18th Century architect, Giovanni Piranese. Marion Harris exhibited his work at the Outsider Art Fair in NYC. In 1992, he received the award of excellence in international competition from the American Society of Architectural Perspectivists. He was also a member of the Blind Artist’s Society.

You had quite a journey, Ian McKay. You were a good friend to many, and always put their needs before your own. I will always remember you sitting in a corner of your neighbourhood restaurant, the Whip, glass of wine and cigarettes at hand. Maybe you are now resting, old friend, in a snug corner of one of your own drawings, telling tales of your grand adventures. You will always be with us.

They are as beautiful in “real life” as they are in photographs. If you didn’t know it was wax, you might think it was a kind of transparent stone. Lovely.

They are as beautiful in “real life” as they are in photographs. If you didn’t know it was wax, you might think it was a kind of transparent stone. Lovely.

I introduced you to the ceramic sculptures of Canadian artist, Serge von Engelhardt, in my last blog. I would like to show you more of his work (e.g., photo to the right). But first, I have something to say about another artist, Eugene von Bruenchenhein (American outsider artist, 1910-1983). I am a big fan of von Bruenchenhein’s work, and his wide-ranging experimentation with painting, sculptures and ceramics. He is generally known for his furniture models made of chicken bones (!) and the photographs of his wife, dressed up as a glamour girl. Like so many other outsider artists, von Bruenchenhein worked at odd jobs to support himself and his wife. He dug clay from nearby construction sites to make his ceramic work and fired his creations in his coal-burning kitchen oven. The grey sculpture to the right is one of his pieces.

I introduced you to the ceramic sculptures of Canadian artist, Serge von Engelhardt, in my last blog. I would like to show you more of his work (e.g., photo to the right). But first, I have something to say about another artist, Eugene von Bruenchenhein (American outsider artist, 1910-1983). I am a big fan of von Bruenchenhein’s work, and his wide-ranging experimentation with painting, sculptures and ceramics. He is generally known for his furniture models made of chicken bones (!) and the photographs of his wife, dressed up as a glamour girl. Like so many other outsider artists, von Bruenchenhein worked at odd jobs to support himself and his wife. He dug clay from nearby construction sites to make his ceramic work and fired his creations in his coal-burning kitchen oven. The grey sculpture to the right is one of his pieces.

was blessed to be contacted by one of Serge von Engelhardt’s daughters. Even better, I had an opportunity to see some of his original porcelain sculptures. They count among the most beautiful creations I have ever seen and I am delighted to introduce him to you.

was blessed to be contacted by one of Serge von Engelhardt’s daughters. Even better, I had an opportunity to see some of his original porcelain sculptures. They count among the most beautiful creations I have ever seen and I am delighted to introduce him to you. One introduction leads to another; that’s how I have been tracking down outsider artists in Canada. Pierre Racine (see earlier blog) suggested that I talk with Luc Guérard in Montreal, Quebec. I discovered a treasure-trove of art on Luc’s

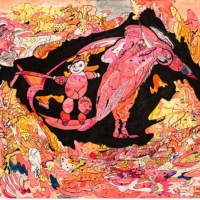

One introduction leads to another; that’s how I have been tracking down outsider artists in Canada. Pierre Racine (see earlier blog) suggested that I talk with Luc Guérard in Montreal, Quebec. I discovered a treasure-trove of art on Luc’s

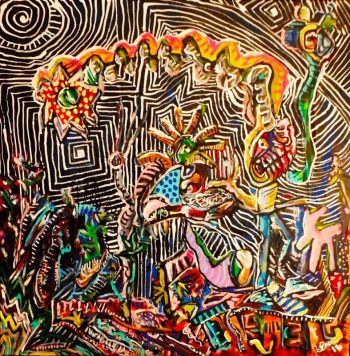

So what do we make of Maka’s art? Is he “just an outsider”, or should he be judged by more traditional standards?

So what do we make of Maka’s art? Is he “just an outsider”, or should he be judged by more traditional standards?